Arts

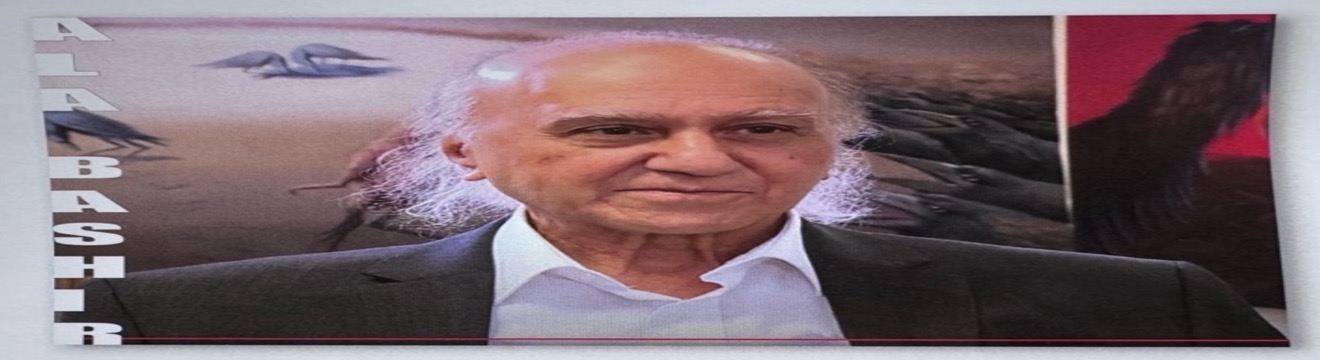

In His New Exhibition, Alaa Bashir Searches for The Savior Dwelling Within Us

Art Exhibition

Dr. Alaa Bashir

Throughout history, across civilizations and cultures, humanity has continuously sought an image of The Savior — that singular being who carries the burden of saving or purifying the world from its evils, not through force or violence, but through something far greater: love, mercy, and forgiveness. This idea, despite its varied religious and philosophical expressions, appears to be a shared human longing — a profound need to transcend the limitations of the self and encounter, within or beyond, a figure capable of reconciling humanity with itself and the world.

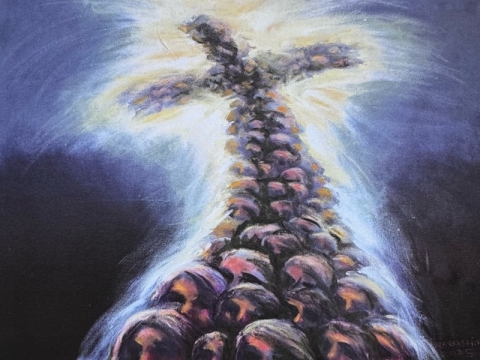

This image is echoed across monotheistic religions but reaches its most prominent expression in Christianity, where Christ is presented as The Savior who sacrifices himself for the redemption of mankind. Yet, the concept of The Savior transcends any single figure. It emerges as an existential stance, a philosophical and spiritual practice that resists humanity’s natural inclinations toward revenge, hatred, and self-centeredness.

It is within this context that the project of Dr. Alaa Bashir — surgeon and artist — takes form. Bashir has chosen to invoke this powerful idea from within a religious tradition seemingly distant from his apparent Islamic heritage. Yet, in truth, he never strays from his spiritual ground. Rather, he revisits the image of The Savior through the lens of his Islamic and Eastern culture. Islam, while not attributing to Jesus (Isa) the theological title of Savior in the Christian sense, presents him as a model of compassion, spiritual strength, and the power of forgiveness. In this way, the two visions converge, dissolving formal differences to reveal a unified human message: that love and forgiveness are the highest virtues attainable by humanity — the true path to personal and collective salvation.

In describing his exhibition, Dr. Bashir candidly admits that this idea has captivated him since childhood. Growing up in a devout Muslim environment may have made this attraction even deeper and more complex, as if part of his soul had always been in dialogue with this figure presented by the religious “other” — not as a threat to his identity, but as an extension of his own yearning for mercy and peace. In his paintings, Dr. Bashir does not present Christ as a historical person or a religious symbol confined to a specific creed. Instead, he portrays him as a living idea, an existential state accessible to every human being — an experience realized whenever a person rises above their ego to forgive, or overcomes their pain to love those who have caused them harm.

What gives this artistic project its profound philosophical dimension is that Dr. Bashir does not present The Savior as an external destiny awaiting us to arrive and change the world. Rather, he presents it as a personal challenge for every individual. Here, The Savior is not someone else, but a potential that lies within us all. The exhibition thus transforms into a spiritual space more than a visual display — a space inviting each visitor to reflect on themselves and ask: How do I embody the role of the savior in my own world? Do I have the courage to love those who have wronged me? Am I capable of breaking the cycle of pain, not through revenge, but through forgiveness?

In this sense, the exhibition becomes a philosophical act par excellence, bringing us back to the fundamental question of the meaning of human existence in a world saturated with violence and hatred. It does so not through preaching or theorizing, but through art — that unique language capable of expressing what words often fail to convey, opening windows of the soul to possibilities we may have never imagined. Thus, Dr. Bashir’s project goes beyond simply reproducing a religious or cultural image. It crafts a human vision that transcends religious and cultural divides, reintroducing the age-old question in a new form: Who is the true savior? Is he a historical figure we await? Or is he a spiritual stance we must each choose to embody in every moment of our lives?

Perhaps this is why Alaa Bashir’s project feels so deeply personal, as if the artist, in practicing surgery to heal bodies, has discovered something even more intricate — the surgery of the soul, the healing of a humanity that continues to bleed from its inability to forgive. His paintings become an extension of his scalpel, and his brush becomes another tool in his quest to heal — not the body of an individual, but the spirit of humanity torn between hatred and love, between pain and forgiveness, between self and other.

Completing the spiritual atmosphere created by the paintings, the audience was treated to another equally profound artistic experience: a gentle piano performance by artist Sultan Al-Khatib, inspired by the Last Supper. The music evoked that poignant moment when the savior gathered with his disciples before embarking on the path of suffering and sacrifice. The performance was not merely background sound but felt like an auditory extension of the surrounding images — as though the music opened another passage into the heart of the experience, reminding all present that the Last Supper was a deeply human moment, filled with fear, betrayal, hope, and a final commandment to love. The music became an unspoken prayer, completing what the brush and colors had begun, enveloping the space in a profound stillness, making the audience themselves feel part of that symbolic feast to which Alaa Bashir had invited them through his art.

Liability for this article lies with the author, who also holds the copyright. Editorial content from USPA may be quoted on other websites as long as the quote comprises no more than 5% of the entire text, is marked as such and the source is named (via hyperlink).